On Beauty

Can we make objective judgments of beauty? Is beauty only in the eye of the beholder? The following essay argues that we can indeed make objective judgments of beauty, although beauty itself is nothing other than a kind of subjective experience of pleasure.

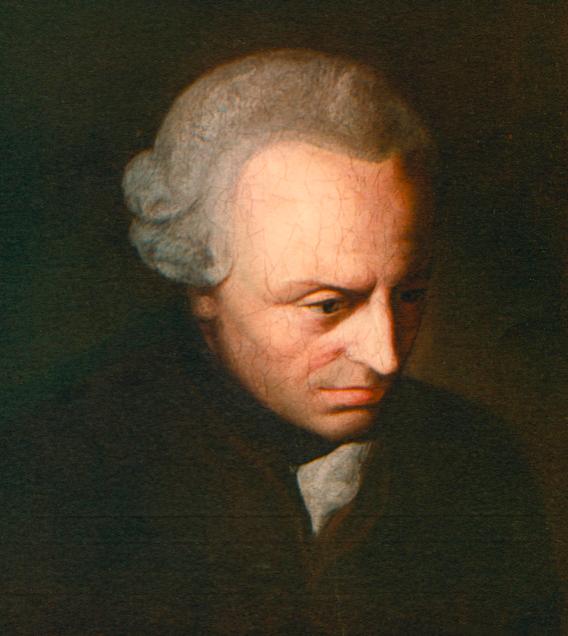

Can we make objective judgments of beauty? Is beauty only in the eye of the beholder? The following essay argues that we can indeed make objective judgments of beauty, although beauty itself is nothing other than a kind of subjective experience of pleasure. The first part of my argument, which relies on the latter claim, is borrowed from the views of the 18th century philosopher Immanuel Kant as explained in his Critique of Judgment. The second part of my argument utilises Kant’s analysis of aesthetic judgments to devise a test for beauty.

If it were impossible to make objective judgments of beauty, then either we cannot make judgments of beauty at all – which is clearly false seeing as we do – or we can only make subjective judgments of beauty. The idea that beauty means whatever each of us judge it to be contradicts the nature of aesthetic judgment in two ways. Firstly, if beauty is only whatever we judge it to be, then it means nothing in particular, which means there is no meaning in describing something as beautiful. Secondly, by describing something as beautiful, we are judging the object as having a certain characteristic. That is, when I say “that rose is beautiful”, I am saying that a particular rose possesses the characteristic of beauty, and therefore that anyone else should judge that rose to have the same characteristic.

However, when we claim something is beautiful, we determine nothing about the concept of the object. What falls under the concept of a rose remains exactly the same whether or not we judge any particular rose to be beautiful. If I tell you I judge something to be a rose, it determines something about the object, but if I tell you I judge something to be beautiful, without telling you anything else, it tells you nothing about how to determine what the object is. In this sense, then, judgments of beauty are not objective, because they do not determine objects. Further, judgments of beauty are singular, whereas objective judgments determine an object under a universal such as the concept of a rose. Without contradiction, I can claim that one rose is beautiful and this one isn’t. I don’t have to claim all roses are beautiful, whereas I can’t claim that a rose isn’t a flower.

Since beauty doesn’t refer to a feature of the object, it must refer to a feature of the observer, and therefore about how we feel towards the object. Further, since beauty refers to what is felt about the object, and not the object itself, the judgment of beauty is indifferent to whether the object actually exists; it is a merely reflective judgment. What is beautiful is always, in some way, pleasant or pleasurable. In summary, to assert something is beautiful is to assert that something gives pleasure by reflection upon it, without reference to a concept, and therefore that anyone capable of aesthetic judgment would take delight in the form of that particular object.

We should take notice that a judgment of beauty is not a judgment of the pleasure something can bring. Beauty admits of a free delight without reference to a purpose other than itself; for example, you want to stare at and contemplate a beautiful painting for no other reason than that it is delightful to do so, whereas you will judge food and whatever brings it to you as likely to bring more or less pleasure depending on how hungry you are. The former judgment is an aesthetic judgment, the latter a judgment of utility. The fact that we often call things beautiful when we really just mean they are helpful or agreeable to our desires should not distract from the prior analysis of what beauty really is. Aesthetic taste cannot be argued nor understood in terms of objective features.

But have I not just argued that our judgments of beauty are subjective? Yes. Is it therefore impossible to make objective judgments of beauty? No. Since a claim of beauty is a claim that something gives pleasure upon reflection to anyone capable, the objective test and rank of beauty is the extent to which this is the case. We must be capable of distinguishing judgments of beauty, which are reflective and conditioned by nothing other than the object, from pleasurable feelings we confuse these judgments with. You may take pleasure in a song due to its lyrics being relatable to your own life or a fond memory of a party or loved one, but that is no demonstration of the art’s beauty. If it were pleasant, though the lyrics were not in any way relatable to you, then you may be judging it beautiful, and it could be beautiful. However, the real test is whether not only you judge it to be beautiful, but mankind judges it beautiful in the same sense; that is, it is continuously pleasant for them to contemplate but as little as possible due to pleasurable associations or purposes.

Therefore, we can make objective judgments of beauty. Among art of similar age, we can judge that which is beautiful to be that which men continue to judge beautiful. Hence, the objective standard of our subjective judgments of beauty is the test of time. Classical music, architecture, and painting devoid of relation to our own context continues to delight mankind, and in centuries to come those songs from our own time which continue to find appreciation will appear most entitled to the claim of beauty compared to those which lasted a few months on the radio. Whether or not we choose to, it is therefore possible to make objective judgments of beauty.

What we have arrived at is both an understanding of what beauty is and a test of what is beautiful. A judgment of beauty is a pleasurable reflection conditioned by nothing other than the object, and hence we can exclude from possible beauty all pleasure brought by association with individual desires or purposes or their unreflective satisfaction. What is beautiful must freely delight men without influence by negative or positive associations specific to their context. The passage of time, which brings with it the waxing and waning of individual and historical influences, is the test which reveals what was only pleasurable due to the context and what deserves the name beautiful. As individuals, we can train ourselves to judge possible beauty by excluding what brings pleasure by association or whetting our appetites, and asking ourselves after passage of time whether our judgments of what was beautiful remain unchanged. We can then ask others to do the same and find whether they agree in their judgment. Of the art, nature, music and architecture preserved for posterity, that which did not or cannot stand the test of time we can soberly reject the beauty of, no matter what pleasure it may have once called forth. Hence, beauty is subjective, yet we can make objective judgments of beauty since we have a standard outside our own taste for determining what isn’t beautiful.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in guest contributions do not necessarily reflect the official positions of Ninth Heaven. We deeply value the insights and creativity of all our contributors. Ninth Heaven exists as a platform for thoughtful discourse and the meaningful exchange of ideas, fostering cultural and spiritual exploration with care, depth, and integrity.