Beauty and the Grotesque: How Art Speaks to the Self

Great art can help us experience our most fundamental humanity.

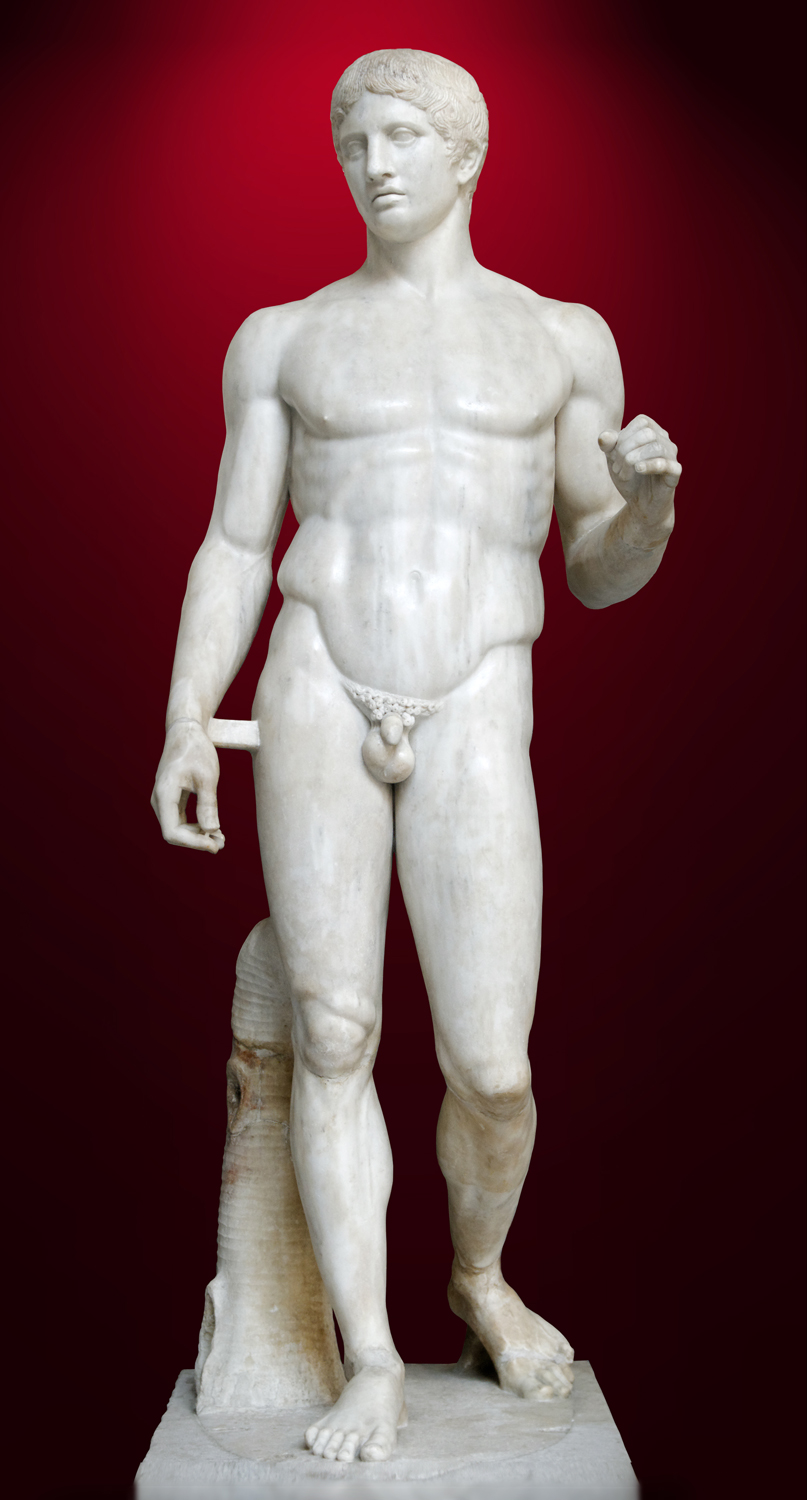

To explore this possibility, I have drawn a comparison between two works: The Doryphoros of Ploykiytos and Chaim Soutine’s 1916 Self-Portrait. These works can show a human conflict between desire and perception. The Doryphoros feigns to be the perfect human form, yet seems alienated from the world of imperfect humans; it is a beautiful surface without a human soul. In contrast, the Self-Portrait is grotesque, consumed by its misery, but this is evidence of internal life. These works engage with the viewer through an exploration of human strife as Gestalt. Gestalt may be understood as a whole that determines or is primary to its parts as they exist relationally. Like the Gestalt, Art can show the inadequacy of single viewpoints. For the Doryphoros of Polykleitos, the single viewpoint that there is a complete and ideal human form shows us the incompleteness of humanity. But while the Doryphoros separates beauty of form from flawed life, awareness is drawn back to the whole, as both fulfilment and unfulfilment of the ideal. Similarly, it could be assumed that the self is the most primary, essential and singular viewpoint. However, Soutine’s Self-Portrait engages with the struggle that the whole of the self is fundamentally unfinished and unseen. The Self-Portrait embodies an awareness that the self, that which seems most known, can never be fully known.

These works may help us grapple with difficult, perhaps unpleasant facets of self and humanity. We want but can never have the perfect, though it draws us towards its beauty, it also withdraws into the unobtainable. Simultaneously, we don’t want to be flawed and incomplete beings. But by dwelling and relating to this uncomfortable reality, there is a possibility for deep connection in imperfection. Part of considering the whole may be in valuing the relationships between self, humanity and art. Perhaps there is an interrelational conversation between these things as wholes made of fragmented, conflicting and irreconcilable parts.

Roman period copy of the Doryphoros of Polykleitos, Naples National Archaeological Museum, Marble, Height: 2.12 metres

The Doryphoros of Polykleitos has come to be understood as a study of the human form as perfection. Although it comes to us as a Roman copy, it is still a work which represents the exemplary skill and vision of the High Classical Greek tradition. This work has become solidified in the Western tradition as the aspirational idealisation of the human form, often known as the Canon. The Doryphoros commands space from all viewing points, in a dynamic, embodied and harmonious manner. Interestingly, though it stands as a dynamic body is not an emotive one. The Doryphoros possesses a total balance and a sense of withdrawn composure. The figure performs strength without strain, power without anger and beauty without vulnerability. His face has a distant, unconcerned, perhaps disinterested quality. He is, as I imagine an immortal would be, regarding the endless toils of mortality.

For me, the Doryphoros embodies a shift in artistic purpose. The longing and reaching forth but never grasping perfection that grounded previous styles in flawed humanity has withdrawn from this work. The Doryphoros is, in a way, the objectification of a human ideal more than a grounding of actual humanity. The seemingly complete composure of the work somehow flattens, as there is no longer depth in unfinished withdrawal. Flawlessness exists in the work, but not outside of it. There is a kind of negation of humanity, for which the work doesn’t feel particularly sympathetic. The constant drive of humanity towards the ideal and the inevitable failure to realise it stands like a Sisyphean task. The Gestalt of this work is the relationship between apparent singular completeness and the eternal incompleteness. The Doryphoros draws the viewer in through a fulfilment of beauty, simultaneously it withdraws from the viewer's frustration.

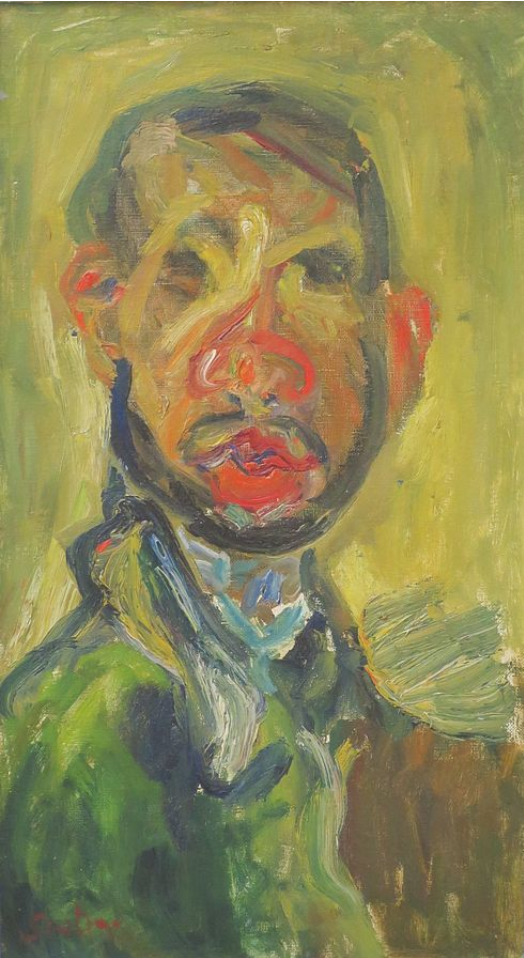

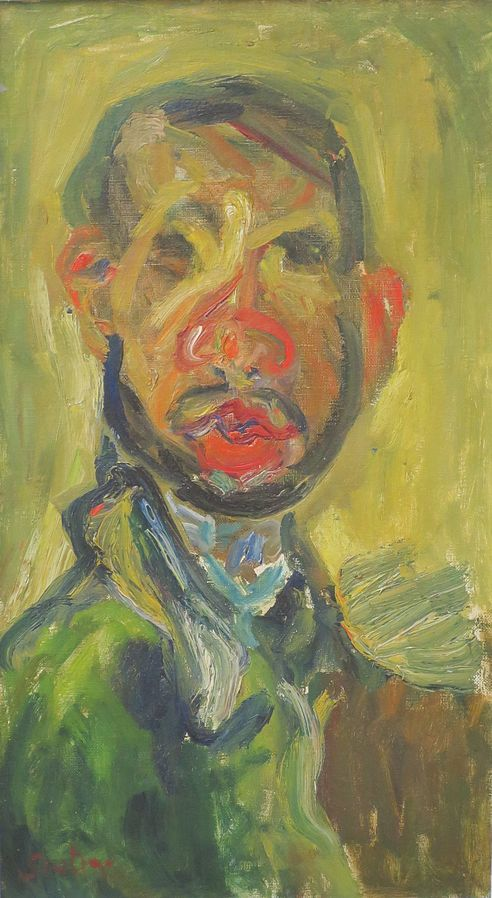

If the Doryphoros is an attempt to perfect the human form, which withdraws from the human soul, its opposite may be the self-portrait. The self-portrait is a style so preoccupied with the self that it may risk isolation through hyper-individualisation. At the same time, there may be something in the flawed individual which is more relatable and accessible than the so-called universal ideal.

On the surface, self-portraits seem to show us the artist as they see themselves. This may be taken for granted as the self is an accessible and available model. The self-portrait appears to fall somewhere in the category of practice, perhaps rawer and more private than what is typically made to be appreciated by others. But the self-portrait may also bring into question how we see others, how they see us and whether we see ourselves as others see us?

The self-portrait is real in its singularity. But it may also possess a universal internal depth that the unreality of the Doryphoros can’t. To see another through their own eyes creates room to relate and reflect on your conception of self. It opens the possibility of seeing how the artist imbues the external with all the shaping burden of the internal. Connection to a self-portrait does not necessarily mean we have the same eyes; rather, we share a common strife. It is this common strife that feels so withdrawn from the Doryphoros of Polykleitos.

What is necessarily the most hidden and private, the internal conception of self, is, in an instant, thrust into the open.

Self-portraiture invites us to see ourselves, but it also confronts our limitations. We exist, yet the whole of our existence is not something even we can fully grasp. The self changes; it seems to be fluid and unfixed, and it must also exist in the minds of others. Which conception is the true self? All and none, it must be the Gestalt, the whole that is primary and never fully grasped. You can never know how you exist in the minds of others, just as you will never hear or see yourself as they do. Perhaps self-portraits then function to bridge the gap and bring into the open that clash between the internal and external.

The self is always there but seems to withdraw from observation that could expose it as ugly, conflicting, raw, textural and uncomfortable. At the same time, the deepest capacity to relate to another is to feel seen in yourself and to see them. This may be why we feel repelled but also drawn in by that internal grotesque vulnerability which sees its kind. I believe this is what drew me to Chaim Soutine's 1916 Self-Portrait.

Self Portrait by Chaim Soutine, 1916, Hermitage, Oil on Canvas, 54x30.5

When I first saw this work, I felt a physical pull of the ugly twisted self dragging me in, and of the beautiful softness which meets the second glance. While this work could be taken as a sad, perhaps dysmorphic conception of self, I find that overly simplistic. For me, it is not necessarily sad, but it is exposed and vulnerable, pulling back into itself just as it bears all. I am so captivated by it; it doesn't feel needy, it almost doesn't want me to connect like I do. It is so caught up in the selfness that it doesn't seem to dwell in the present. And in this way, I feel as though I am humbled and ignored by the artist's humble devastation. The eyes are so withdrawn that they are almost imperceptible, as though the self is withdrawing. The soft, thick, greeny yellow melts into space, as though the figure wishes to be pulled into the ground, yet reluctantly stands apart from it.

I find the way the warm vermilion brings life and attention to the lips, ears and nose so human. Yet there seems a clear disdain for self in the work, the over-emphasis of parts shows, I think, the way the self does distort its conception of the external. The sincerity of the work allows the essentially human to shine forth. This work seems bright with colour, the pure brushstrokes shine forth boldly, but also smudged and dampened. It possesses both the freshness and boldness of line and the labouring of unsure overmixing, fiddling with the colours until they lose all form. For me this is a beautiful expression of the complexity of self, that it holds great joy and sadness, skill and insecurity. I think this work would be easier if he were beautiful, calling to be seen and demanding all the attention. Instead, there is an uncomfortable amount of space for the viewer. But I think it's the discomfort and presence of self that draws in and holds the viewer.

I wonder if people were critical that Soutine’s work was not enough like him. Did he feel it was or not quite yet? Would the work that others deem likened to you be one you can understand as self, or is your relationship with yourself so counter to others' conception of you? How can a self-portrait ever not be alike? For me, the failure to observe the self, through contempt, pride, shame or external expectations, is necessarily a reflection of the self. The cruel exposure of the self that would rather remain hidden, yet is likened, whether it is explicit or withdrawn.

The evolution of an artist's life through self-portraits documents change, beyond the effects of time; it typically documents the evolution of practice. But perhaps it documents the evolution of self, the deepening of understanding of self, the remembering and forgetting, reaching forth and falling back. I wonder if the artist becomes weary of self-awareness and tries to repress or alter the form. Does the self accept or reject this?

If the artist captures a deep resemblance in the work, does it make them shiver with eerie discomfort, wishing they had never done so? Soutine’s self-portrait possesses fluidity and fluctuation. It's not fixed in stone but imbued with the movement and restlessness of the self.

Art like the Doryphoros attempts to create beauty in perfection. Though the Doryphoros achieves a pull towards the enjoyable, the external composure is like a facade. As the perfect pulls you in, its humanity withdraws, and the incompleteness is inaccessible. The pleasure of the encounter is in the skill and vision, it leaves an awe, but may not possess like art that is steeped in the tension and discomfort of being. The Doryphoros is a dream; instead, Soutine grounds the viewer deep into the internal. Through these works, a human strife is shown between the unattainable desire and the perception of imperfections, which may bring fulfilment. Art is capable of creating visions that speak to the aspirational, beautiful, masterful and transportative dreams of humanity. But art can also create room for a deeper and more vulnerable understanding of commonality with another, and perhaps our own self. If the Doryphoros is a beautiful facade, which the self cannot penetrate, Soutine's portrait is like a cave pulling you towards the darkness.

Art can be seen as a reflection of humanity, or of self, but it could also be the relational conflict between the three. The Doryphoros of Polykleitos can be understood as a human endeavour for perfection and perhaps immortality. But the Gestalt of the work may be seen in the fulfilment of this dream, and the failure. The still idealisation of the human form must show itself in relation to the flawed and mortal viewer. Soutine’s self-portrait so brutally exposes his flawed and imperfect humanity, so that it may, on first encounter, clash against the instinct to find the beautiful. However, its Gestalt allows the viewer to find grace and beauty in their own imperfection and internal strife. The work of art can be seen as the relationship between form, creator and audience. In this relationship is the ability to create, explore and uncover. Perhaps works of art, just as humanity and the self, are relational wholes made of fragmented and conflicting parts in a constant flux of revelation and concealment.