A Chance to Make It

Cosmic re-enactment in the path of Ars Regia.

From time immemorial, we’ve sought answers in the stars. A scientist may call it a ball of gas, to a medieval saint it’s a celestial body in the heavens, but to many children like Charlie Brown of the comic strip Peanuts, they’re a mystery to be grasped. Babies often reach up towards shiny objects, lights, and moving things in the sky, which draw their attention with a sense of curiosity and awe. In a world seemingly drained of its mystery by scientific innovations and light pollution, the youngest of us are always booming with fascination for the unknown. But our era poses a problem for them. What meaning is to be found in the stars? To a boy like Charlie Brown, no conceivable answer is ever satisfying.

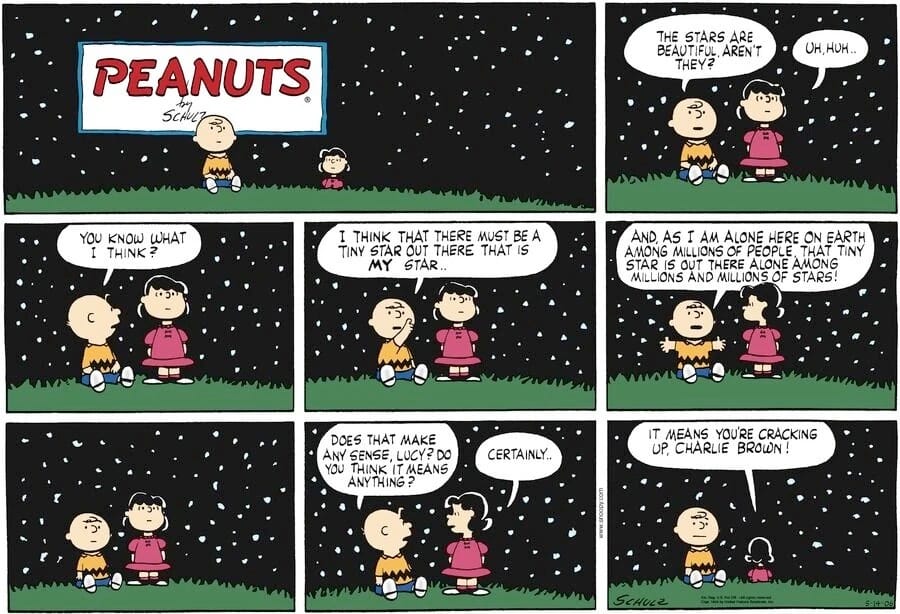

Peanuts is a story with little to no victories. Each comic strip is a series of failures and questions left unanswered. It’s a story of deep suffering, and in a comedic twist, its protagonist is often the butt of its jokes. Charlie Brown is the subject of much pain, verbal abuse from his peers, existential dread, and a world indifferent to his troubles. In much of the comic, he’s shown as depressed, melancholic, and listless. As Charles M. Schulz the author of Peanuts says (1975), “Charlie Brown must be the one who suffers, because he’s a caricature of the average person.” He struggles, he fails, and tries to make sense of himself as a secular soul in a secular universe with no space for wonder. Yet in his doubt and melancholy, there is a hesitant hope. A cry out to the cosmos. “Sometimes I lie awake at night, and ask, ‘Why me?’” He asks in one comic strip (Schulz, 1993). In the stars, he searches for an answer. “There must be a tiny star out there that is my star,” he thinks in another (Schulz, 1959). It’s a yearning for self-assertion poured out in existential angst. That despite his alienation in a seemingly endless void billions of light years from one end to the other, there is a star just for him shining in the firmament.

How the ancients conceived the universe

Today we see the sky as a clear mostly empty space, but to the ancients it hovered above them as an arched vault in and of itself, an expanse they called the firmament. What lay beyond it was a mystery, but they all understood that there was something beyond perception that the firmament was keeping the world from seeing. The idea of the firmament is present in ancient cultures throughout the ancient Near East. The first recorded instance of this cosmological theme is to be found in Babylonian literature, in the epic Enuma Elish. Its telling of the world’s creation is a violent one. The god Marduk slays Tiamat, a being of the primordial waters, and fashions the cosmos from her corpse by splitting her body in two. One half comes to form the firmament, the ceiling of the sky above which her primordial waters are sealed, while below he makes of her the earth. A divine act of separation is imposed on the universe to make order out of chaos.

This triumph of order over chaos is echoed in the act of creation seen in the Jewish and Christian traditions in the book of Genesis when God separates the waters of the primordial abyss (New International Version, 2011, Genesis 1:6-8), making between them the firmament:

And God said, “Let there be a vault between the waters to separate water from water.” So God made the vault and separated the water under the vault from the water above it. And it was so. God called the vault “sky.” And there was evening, and there was morning—the second day.

The cosmic order embodied by the firmament had profound implications for ancient man and went on to shape their entire world-picture. The heavens revealed to him signs, as Genesis (New International Version, 2011, Genesis 1:14-15) further elaborates:

And God said, “Let there be lights in the vault of the sky to separate the day from the night, and let them serve as signs to mark sacred times, and days and years, and let them be lights in the vault of the sky to give light on the earth.”

There was a logic, reason, and purpose for all entities across every cosmic sphere. Meaning imbued the horizons, and a sacred alignment was found between the heavens and the earth. The eye of providence was reflected in the stars and revealed the course of creation. Astrologers and priests would look to the stars for guidance, instructing them in the ways of agriculture, ritual, law, kingship, and even the very anthropology of the human soul. In the heavens there lay the answers to all of life’s mysteries and deepest problems. As put by the famous Hermetic principle, “as above, so below.” The world and mankind may be fallen and imperfect, as the world’s traditions tell us, but the solution is right above us if only we can restore ourselves to its eternal principles. Man, troubled by his limitations, sought reasons for his state of being and a remedy to it, and in turn, took part in this divine act of discerning order from chaos.

This encounter with chaos is the major ordeal of every hero’s journey, and it is as much an inner conflict as it is an external one. Man’s fallen nature required redemptive measures. Death, illness, and all failure hinged on man’s own responsibility. Nothing was an accident. This wasn’t determinism, but the duty of an active agent in an ordered universe, as expressed by the theologians of the Catholic tradition, from Augustine to Aquinas. These struggles echo through all human existence and we project them onto our art to confront and understand. In Peanuts, Charlie Brown finds himself lost continuously in unfair failures without any apparent logic, from getting his kite stuck in a tree to his failures in baseball. “Everything I touch gets ruined,” he says in the 1965 animated television Christmas special. But he nevertheless searches for patterns in these struggles. He recalls the kite eating tree, he remembers that Lucy always yanks away the football when he tries to kick it, and he questions his own character flaws to identify a root cause. Mankind is made to seek order amid chaos, and doing so is the only solution.

Dante Alighieri’s descent and ascent from the first hell to the ninth heaven

The idea of an ordered cosmos surrounded by a firmament separating the heavens and the earth continued into the Middle Ages with the geocentric worldview of Ptolemy and the astronomers that came after. The earth took the centre of the universe with heavenly bodies occupying concentric spheres that revolved around it, each in succession according to hierarchical perfection. In his Divine Comedy, Dante Alighieri conceives a hierarchical universe, himself progressing through the successive realms of the Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso which within themselves are found nine, seven, and nine layers respectively. Like the theologians and astronomers before him, Dante conceived the heavenly spheres as the bearers of eternal light and truth governed by divine intelligence. But where those who came before him systematised the heavens, Dante builds a living human world around this system, with man as the subject who must venture the fires of hell to achieve spiritual awakening.

Many of us know very well the tales of those who attempted to take heaven by storm and failed miserably, as the Bible tells us in its same Genesis with the fall of the tower of Babel and Greek mythology warns us very clearly with the tale of Icarus whose wings came apart when he flew too close to the sun. Yet reaching the Empyrean, the abode of God, is precisely the journey that Dante sets out on.

Where the circles of the Inferno and Purgatorio are separated by material barriers, the planetary circles of Paradiso are graded by virtue following the Ptolemaic geocentric model: the Moon corresponds to the inconstant in faith, Mercury corresponds to the ambitious, Venus corresponds to the lovers who loved too deeply, the Sun corresponds to theologians and the wise, Mars corresponds to the virtuous warriors of Christendom, Jupiter corresponds to the just rulers, Saturn corresponds to monks and contemplative souls, the fixed stars correspond to the virtues of faith, hope, and love, the Primum Mobile is the sphere that moves all others spheres and corresponds to the angelic hierarchy, and the Empyrean where Dante achieves the Beatific Vision is the abode of God.

By systematising the heavenly spheres according to their symbolic virtues, Dante’s Paradiso entails a complex set of relationships between the heavens, mankind, and the world. In his study of Dante, the French metaphysician Rene Guenon (2000) suggests that the circles of Paradiso are symbolic superior states of being and that in his ascent, Dante’s initiation is an active conquest of the supra-human states. Heaven and hell in the Divine Comedy are not merely the result of a life already lived, but latent realities that Dante as the hero may journey through. In the poem the characters he encounters may have already passed from this life, but in journeying through these states of being while still living, Dante’s journey opens the door to profound truths of the soul’s transformation which every soul may undergo the initiatic process of in this life.

To the mankind of medieval Christendom, the stars were is not a distant reality as it may seem to modern man and his longing avatar Charlie Brown when he considers the enormity of the universe and his insignificance as a tiny unseen speck amid its backdrop, but an immanent force in the human soul both ever-pervading and yet latent as an ideal to aspire. In ancient times prior to Ptolemy’s formulation, it was already believed that man could achieve a place in the stars as the souls in Paradiso did. When a Roman emperor died, an eagle was released above the ashes of his body on the funeral pyre to carry his soul to the heavens. Moreover, in Book 15 of his Metamorphosis, Ovid speaks of the deification of Julius Caesar and how the goddess Venus took his soul from his corpse and made it into a star in the heavens. Thus, it was believed throughout the ages that man, by virtue of his deeds in cooperation with the grace of divine forces, could reach beyond the firmament. Mortal could become immortal and the fallen could be redeemed. In such a reality, Charlie Brown in his wistful yearning would finally be given the possibility of discovering his star among all the million other stars, and even more, become that star himself high above in the firmament.

Towards the 16th century, however, the geocentric worldview came to be challenged by alternative scientific theoretical frameworks and observations that resulted in the breakdown of all the metaphysical and anthropological assumptions that the geocentric worldview implied. This transition would be later dubbed the Copernican revolution during the enlightenment, after Nicolaus Copernicus and his heliocentric model, which placed the sun at the centre of the cosmos. In popular culture, Copernicus’ theories are often seen as just the turning point when an outdated model of the solar system made way for a more empirically accurate model. However, the truth is that when compared to Ptolemy’s model, Copernicus’ heliocentric model was no more accurate in making astronomical predictions about the positions of the celestial bodies and was not simpler (Kwok, 2017). This was primarily because he was still relying on circular orbits as opposed to the elliptical ones that Kepler would later introduce. Really, Copernicus was motivated by the idea of a rationally ordered cosmos without the equant and reworked the epicycles of the geocentric model (Nickles, 2002). But despite his alignment with traditional metaphysics, Copernicus’ project would ultimately lead to the loss of any perspectival reference from which the universe could be perceived from on objective and absolute terms. What emerged was a relative universe within which there is no centre. As Goethe said of Copernicus (Kwok, 2017):

Among all the discoveries and beliefs, none have resulted in a greater effect on the human mind as the doctrine of Copernicus.

While Copernicus and his successors, Kepler, Galileo, and Newton, did not abandon the idea of divine harmony in the universe, the metaphysical and anthropological consequences of the loss of an absolute perspectival reference were to be felt in the wider popular consciousness. Man was displaced from the centre of the universe and earth was merely one out of many planets in an infinite void. The celestial bodies lost their symbolic weight as bearers of divine truths and were now merely made up of physical properties no different from the ground that man stands upon. Secular man was cut off from his traversal through the heavenly spheres and was made distant from the stars above. As Charlie Brown’s best friend Linus van Pelt puts it plainly (1957), “Doesn’t looking at all these stars make you feel sort of insignificant, Charlie Brown?” And as Charlie Brown suggests himself in another comic strip, the big dipper will fade away in another hundred thousand years because of the unequal movement among its stars.

However, it is also precisely this relativisation and crisis in orientation that Dante finds himself in at the beginning of the Inferno. Inherent in his journey is the need to first descend into the underworld before ascending to the heights of Paradiso, as Virgil explains to him in Canto I:

Therefore, for your own good, I think it well

you follow me and I will be your guide

and lead you forth through an eternal place.

There you shall see the ancient spirits tried

in endless pain, and hear their lamentation

as each bemoans the second death of souls.

Next you shall see upon a burning mountain

souls in fire and yet content in fire,

knowing that whensoever it may be

they yet will mount into the blessed choir.

To which, if it is still your wish to climb,

a worthier spirit shall be sent to guide you.

Dante must confront the suffering of the damned in consequence of their sin. But why? The tradition of Ars Regia of which Dante was continuing may give us clues. Before encountering Virgil, Dante finds himself in a dark wood, disoriented and lost from the straight path of righteousness. He, like those he’ll observe and speak to under the earth, is deep in his sins which threaten to consume him like ravenous beasts, the leopard, lion, and she-wolf hunting him down representing incontinence, violence, and fraud respectively. Virgil, symbolic of archetypal reason, is the guide who may lead him to Beatrice, the “worthier spirit” he mentions. Reason must guide him because it is the mental faculty capable of discerning order amid chaos, allowing its traversal. In the tradition of Ars Regia, the first stage of the alchemical process is the nigredo, or “blackening”. It is the stage that initiates transformation in the Magnum Opus (Great Work). It is a disintegration of the ego to the point of death, a stage of putrefaction in which one’s self-conception, illusory and bound by imperfections, must decay before the psyche, the Prima Materia (raw undifferentiated matter) of this work, is transfigured in the later stages. The descent into hell is necessary for Dante’s own reintegration. It is only by confronting sin, purging its latent possibility, and exhausting its power, from the lower circles of incontinence to the deep cold abyss of fraud and treachery, that the soul may come to realise the extent of its fallenness and make its way up to the highest stars of Paradiso. As Rene Guenon discusses in his book the Esoterism of Dante (2000):

The descent allows the manifestation, according to certain modalities, of the possibilities of an inferior order that the being still carries in an undeveloped state, and that must be exhausted before it can attain the realisation of the higher states.

These higher states, of course, are the supra-human states of being that Dante transcends to in Paradiso. This corresponds to the rubedo, or “reddening” of alchemy, as the final stage where the spirit is reintegrated with all of man’s constituent elements, bringing man’s entire anthropological make-up into wholeness and completion. Between these contrasting realities, however, the dross must be swept away, and the soul must be cleansed and illuminated before it reaches heaven. This is the albedo, or “whitening” of the Magnum Opus. In Catholic doctrine, purgatory is taken to be an intermediate state after death in which the soul in a state of grace is purged of its past sins before it enters heaven. Dante, however, situates Purgatorio on a physical mountain connecting the earth and the firmament. This places the dead souls in a similar situation to our own, with the perspective of viewing the celestial bodies from below. It is here that the initiatic path to transcending mundane reality is opened through the vertical axis in the ascent of this mountain. The physical narrowing of the mountain as one ascends upwards signifies the return to divine simplicity, from multiplicity back to unity. This is made especially clear as the angels progressively clear the marks of the seven deadly sins from Dante’s forehead at each stage of the ascent, starting from pride as the root of all sin to the most easily redeemed sins of avarice, gluttony, and finally lust.

In his essay ‘Because Dante is Right’, the Swiss metaphysician Titus Burckhardt (2003) describes the punishments of Purgatorio as “stages of ascesis” in which man is led back to the primordial Edenic state wherein his knowledge and will are reconciled. He interprets the punishments of Purgatorio, as Guenon does for Dante’s descent into the Inferno, as a gradual exhaustion of sinful impulse. The difference in Purgatorio is the apophatic realisation indirectly through the pain of sinful concupiscence as a privation of good, what the divine good and therefore good-willing freedom truly is. Knowledge of the good is paired with will towards good. Thus, because this sinful concupiscence is exhausted, the peak of Mount Purgatory denotes the original state free from concupiscence: the earthly paradise of Adam and Eve. Burckhardt (2003) summarises it beautifully:

The soul’s reality now opens out on a cosmic scale, embracing the starry heavens, day and night, and all the fragrance of things: at the sight of the earthly paradise on the summit of the mount of Purgatory, Dante conjures up in a few verses the whole miracle of spring; the earthly spring turns directly into the spring of the soul, it becomes the symbol of the original and holy state of the human soul.

The location of primordial mankind at the precipice where heaven meets earth implies here the condition for which having left behind every deformity, the soul is now capable of inheriting the higher principles of the celestial bodies to live in and through the human person. During his General Audience on August 26, 1998, Pope John Paul II reflected that “God wants to communicate himself. This divine self-communication takes place in the Holy Spirit, the bond of love between eternity and time, the Trinity and history.” He subsequently reminds us that man is “capax Dei” (capable of God) and thus capable of knowing God and receiving his gift. This gift that God bestows on us is the seven gifts of the Holy Spirit: wisdom, understanding, counsel, fortitude, knowledge, piety, and fear of the Lord. These transformative divine gifts are revealed to Dante in the heavenly paradise when he witnesses a procession led by the seven golden candlesticks of a candelabra that at first due to their distance appear as trees. This initial mistaking of the candlesticks for trees calls to mind the tree of life as the vital principle of cosmic manifestation, with the fires of the candelabra representing the light of pure forms on the terrestrial plane. Dante is thus illuminated by this light and becomes a vessel for these gifts. Further symbols hence appear in the procession such as the three theological virtues and four cardinal virtues. What this implies is that man as the image of God, whose soul is situated where heaven and earth meet, can inherit the gifts of heaven which live in and through him, joining the celestial and terrestrial planes.

In traditional metaphysics, the soul is perceived as the midpoint between matter and spirit as part of the three-fold nature of man. No matter the physical distance between himself and the stars, modern man is eternally in his anthropological make-up capable of discovering the virtues that the celestial bodies once symbolised in the past within himself and participate in divine life. The kingdom of heaven not a distant reality, but as Christ tells us in Luke 17:21 is within us. Saint Teresa of Avila would later describe the soul as an interior castle wherein it is transformed in union with God at its deepest centre, which is preceded by the spirit’s flight and elevation. Dante’s Paradiso, too, would end with his union with God, symbolising the completion of the Magnum Opus where the integration of the body, soul, and spirit is fulfilled in the unity of heaven and earth.

Perhaps the most holistic example of this unity can be found in the writings of Saint Hildegard von Bingen. Her thought exemplifies the medieval microcosm-macrocosm idea in its most vivid articulation and symbolic clarity. Her corpus covers a wide range of disciplines, bridging theology, anthropology, mysticism, medicine, and even music, all integrated within a framework that conveys the cosmic unity of microcosm and macrocosm, the heavens and the earth, the eternal and created, the universe and man. In Hildegard’s anthropology, all elements of the cosmos are to be found within man. Within her framework of the human body, the four humours are analogous to the four elements and their respective qualities. The heat, coldness, moisture, and dryness of the elements at play in the body are to be brought into harmony in emulation of the cosmic order. These elements also influence and disturb the actions and impulses of the will in a way that mirrors their interplay within the terrestrial world, as she illustrates in an analogy in her Book of Divine Works:

Indeed, the earth is cracked by an excess of the sun’s seething heat, and cannot usefully raise a bud because of undue rain; instead, the earth sprouts whatever things are useful through the proper balance of heat and moisture. So too through just moderation all the works of heaven and earth are ordered and accomplished well and with discretion.

The united soul and body reciprocally affect one another, as the excesses and deficiencies of the body affect the soul’s discretion. The key to the life of either is the life of the other. Likewise, the concordance of both reflects the harmony between the heavens and the earth. The whole cosmos is contained within the microcosm of man, including even the firmament as she relates in the same book:

The whole human body is joined to its head, as too the earth, together with all its appendages, clings to the firmament; and the whole human person is governed by the head’s sensibility, just as each of the earth’s functions is fulfilled by the firmament.

The journey beyond the firmament finds its passage within. Just as the order of the cosmos fulfils the earth’s functions, the rational principle of the human person takes its hierarchical precedence over the rest of the body. She writes also that the “soul is diffused throughout the entire body, just as the windiness of the winds roams throughout the entire firmament.” That our soul takes precedence over even the firmament, implying its superiority as the vital animating principle in the human being. Thus, the purgatorial journey of self-reorganisation is likewise the bringing into order the harmony of the cosmos from its previous chaos. He must save the world within himself. But does this imply he holds the reins to his own salvation? Saint Hildegard certainly wouldn’t agree, but this dilemma would make way for the intellectual tension between the optimistic sentiments towards human nature and realism about sin in the coming centuries.

The Genesis of our age and will man make it before its end?

So where is modern man’s place in all this? We learn that it is reason, Virgil, who guides Dante through the Inferno and Purgatorio to achieve his ascent to earthly paradise, and yet where is the reader’s victory who received in Dante’s wisdom? Is he not transformed by divine wisdom like Dante is? Is he not transformed by the divine beauty for which Dante’s poems play a medium? And in his life, does he not suffer and protest to the universe for answers? Where is salvation for modern man? For Charlie Brown, who certainly faces life and suffers? In the century after Dante’s death, Italy witnessed the rise of the humanist philosophy, which while continuing his vernacular tradition, shifted thematically in a secular direction with a greater emphasis on individual subjectivity, beginning with the works of Petrarch. The Swiss historian Jacob Burckhardt, famous for his The Civilisation of the Renaissance in Italy (2000, Part 4, Chapter 3), would call Petrarch one of the first “truly modern men”, referring to the “indescribable longing” and the enjoyment of natural beauty as aesthetic object present in his Ascent of Mount Ventoux. Italian humanist Leonardo Bruni would credit him for the renewal of Latin eloquence as the founder of the humanist movement only decades after his death (Ianziti, 2005). Petrarch certainly marks the point of a transition, and like Charlie Brown, he felt himself out of place in his own era. This stirred a love for classical antiquity that pervaded his work throughout his life.

His time saw a decline in the political tradition of universal Christendom that had been the unifying ideal since Carolingian times, following the Great Interregnum proceeding the extinction of the Hohenstaufen dynasty, the rise of the third estate, and the increase of political independence among the Italian city-states, which Dante himself would have seen emerging in his lifetime. In his biography, Letters to Posterity (1898/2001), he’d refer to Avignon, the seat of the Papacy, as a “disgusting city”, and in the same text speak of his general disliking for his own age which drew him to the study of antiquity. But this deep crisis in Christendom did not mean the end of the Middle Ages. The feudal system continued, scholasticism reigned in academia, and while in decline, chivalry was still in the popular consciousness. This left him alienated from both the changes of the times and the not-so-distant past, an alienation leading to both his radical intellectual independence and the longing of his aching soul. The world-picture of Catholic universality exemplified by the thought of Dante and Saint Hildegard, and all its political, cosmological, and anthropological implications were known to and believed by Petrarch, and yet in his heart he seemed almost to speak from a different outlook. If he really is the beginning of modernity, he is also its first victim.

Despite being proclaimed by historians as the beginning of the humanistic ethos, the Ascent of Mount Ventoux carries traces of Dante’s own ascent of Mount Purgatory. The spiritual journey, the moral self-reflection. They’re both present. But where Dante is on a progressive ascent closer to the firmament, Petrarch’s ascent draws him inward. Not towards heaven, but into the restless hum of his inner world, ending in the self-awareness that in his outward yearning he neglected his own interior life. This egoic impulse to gaze into one’s mirror echoes into modernity. The lonely monologues of Charlie Brown and his unanswered self-criticisms see their predecessor in a man living in a world not yet so withdrawn as he.

But is the source of Petrarch’s longing merely in his mental disposition as a man at the threshold between tradition and modernity? What is the object of his longing? Perhaps our best clue is his Canzoniere, a series of poems written throughout his adult life. Petrarch’s poems follow in the tradition of courtly love, with many poems in praise to his muse Laura much as Dante’s poems to Beatrice in his La Vita Nuova. She is of course a central theme to his poems, yet her character lacks any distinct traits, dialogue, or emotions. Like Beatrice, she is a symbolic avatar for Petrarch’s longing and all the ideals he pursues. But whereas Beatrice’s role as a symbol of divine wisdom is clear in the works of Dante, Laura’s meaning is more elusive, changing, and ambiguous. In Peanuts, Charlie Brown has his own unrequited crush: the little red-haired girl.

Like Petrarch’s Laura, the little red-haired girl often appears in parallel to moments of depressive reflection for Charlie Brown, in his loneliness, his melancholic state, his poor self-image. “I’m always thinking about that little red-haired girl, but I know she doesn’t think of me,” he says in one comic strip (Schulz,1978), “because I’m a nothing and you can’t think of nothing!” Yet not once has he ever spoken to her nor does he know anything about her. Like Laura, the little red-haired girl is only shown in the comics as an object of Charlie Brown’s projections.

Like Charlie Brown in Peanuts, defeats are numerous over the course of Petrarch’s poems. But they are all defeats of the soul. His first poem begins by expressing “the sound of sighs with which I fed my heart” and how often he feels put to shame by the praises of others. In poem 11 he describes a veil that “rules him”, blocking the “sweet light of her lovely eyes”. Until then he says that he’s never seen her “remove that veil of hers” and that upon the sight of her gaze, he was so struck by the mere short glimpse that upon its loss he feels a profound frustration for a veil that represents a sense of distance and unattainability. This sense that the object of his desire or interest is out of reach permeates throughout his poems, not just for Laura but encompassing a major theme. But given her lack of any character traits, what is it that he vaguely perceives in her? Only glimpses are caught and only a vague silhouette of her true archetypal identity is revealed. This lack of characterisation is present even in her appearance. Whereas the clothes and self-conduct of Dante’s Beatrice are shown, the beauty of Laura consists in no more than her eyes, face, hair, and other bodily features.

Despite Laura’s elusive and mysterious nature, love remains Petrarch’s motivating force. To him, she is almost a psychopomp, like the Valkyries of Norse religion. A divine lady of the soul’s transformation as in chivalric romance and archaic myth. In poem 129, he describes that in his lonely wanderings through mountains and woods, urged on by love, he wonders, “perhaps, you're loathsome to yourself but dear to her (…) Now could this be the truth? But how? But when?" In the same way that Charlie Brown torments himself with questions of why and potential guesses that are never confirmed. Petrarch then describes how he perceives her face in the stones he comes by and when returning to reality he cries, “What have you come to? How far from her you are!” Then elaborates how many times he’s seen her many times “in the clear water and above green grass”. Almost in the way that mystics like the Dominican Meister Eckhart perceive God in all things, but in Petrarch’s case this brings him great pain and instead of grasping the truth, it eludes him.

Given the existential nature of Petrarch’s poems, it seems that in projecting his inner conflicts he expresses the post-fall condition of the human soul. To struggle with unfulfilled answers, to protest, “I want to get what this all means.” This is more than humanistic or modernistic subjectivity. Inherent to our subjectivity is the distance between man and the objective whole. The distance between man and the cosmos, the distance between man and the holistic truths of Dante and Saint Hildegard. Poem 15 of Petrarch’s Canzoniere expresses it clearly:

With every step I take my weary body,

which I bear with me in great pain, turns back,

then from the air around you I take strength

to move it onward and say: "Woe, poor me!"

Then thinking of the sweet good that I leave,

of my long journey and of my brief life,

I stop short in bewilderment, and pale,

I look down at the ground, my eyes in tears.

Sometimes amid my sad laments a doubt

assails me: how can all these parts of me

survive so far away from their own soul?

But then Love answers me: "Don't you remember

it is a privilege granted to all lovers,

to be free of all human qualities."

The weariness of his aching heart, his confusion, his attempts to grasp the transience of life, and that question, “how can all these parts of me survive so far away from their own soul?” It almost signals the coming dualism of Descartes and an inner fragmentation where the previous unity of body-soul-spirit has come into disharmony. The confrontation with transience, too, pervades many of his poems. The inevitability of death is also a certainty he struggles with, particularly the eventual death of Laura, whether real or symbolic. Whereas to Dante, the question was the eternal, not the transient. While he does contemplate eternal and divine things, his disposition to subjective sensibility, earthly beauty, and his conflicted nature expresses his forlornness. His awareness of the sacred is nowhere near absolute.

The question arises: how will he make it to God? How will we all make it? The whole left fragmented, how is it to be reintegrated? Is it possible to make sense of the infinite? Of the entire Truth? Human experience tells us no. Man is a finite being. But he still ought to reenact the cosmic order in full splendour. It’s a matter of life and death.

Petrarch, like Charlie Brown, surely struggled and persevered through his failings like the souls of Dante’s Purgatorio. As a well-educated man, he was definitely aware of the metaphysical world-picture perpetuated by the academia of his day and its Catholic universalism despite his ambivalence to it. Then what was he missing?

Since the reveal of Laura’s death in poem 267, she becomes more out of reach to Petrarch, yet her status is elevated, and her presence endures. She is sanctified and he declares her heavenly fate certain. The distance between them is made greater, and by expressing her absence in his life she becomes a symbol of unattainable divine beauty through the loss of her earthly form. But the longing and suffering of this distance kindles the desire for transcendence. “I thought my wings were strong enough to soar (not by their power but by his who spreads them)” he says in poem 307, implying that implicit in his longing is an understanding of his own faultiness. The theme of transience begins to take a more spiritually self-critical turn, lamenting in poem 319 how “no good lasted more than a wink”, and exclaiming, “O wretched world, changing and arrogant, a man who puts his hope in you is blind.” However, he also suggests in the same poem that his spirit is still bound to Laura in her transcended being, “But her best form, which still continues living and will forever live high in the heavens, makes me fall more in love with all her beauty.” Thus, her death becomes a catalyst for which his attention is drawn to more spiritual things, but still only in a narrow sense insofar as it relates to her new transcended beauty.

Petrarch yearns for death to close the distance between them on multiple occasions, as he does in poem 332, “and so now I have turned to begging Death to take me from this place, and make me happy, to her for whom I sing and weep in rhymes.” But ultimately, he does not desire heaven in itself until a breakthrough occurs in the final poems, as in the 362nd, “With wings made of my thoughts I fly to Heaven so often that I almost think I'm one of those who have their treasure with them there, now having left on earth the rendered veil.” Referring to the same veil of poem 11. The reflective and regretful tone of his poems, moreover, gain greater spiritual clarity, as when praying to God in poem 365 he goes on, “lamenting those past times I spent in loving something which was mortal instead of soaring high, since I had wings that might have taken me to higher levels.” Thereby openly regretting having desired the earthly and narrowly-oriented love for which he beheld Laura, hindering his spiritual growth. Then finally in the last poem, 366, he makes a petition for mercy to the virgin Mary as the queen of heaven for the life he had lived.

Unlike Dante’s Divine Comedy, there is no rubedo, no ascent into the firmament, just a decisive shift in the final poem. But this is a proper and necessary shift. What occurs that was once missing is sacrifice. To let go of old impulses and desires like Dante gave up as the angels removed the marks of the seven deadly sins from his forehead in his ascent to Mount Purgatory, his albedo. In a sense, Petrarch does undergo the nigredo and albedo of the Magnum Opus through his sufferings, his confrontation with himself and his past, and the inward shift expressed in his poems.

Modern man, as Petrarch accepts, must make room for grace and allow for its inner working through sacrifice and make an active participation in that grace. But modern man faces the same problem as Petrarch to a much deeper degree; how can a world-picture be willed in one’s life and being in a world and society that doesn’t match it? Petrarch’s time saw the decline of a previous universalistic political ideal, but at least it persisted. In our time, holism has been vastly disregarded in secular life. While the Catholic Church’s own canon law and catechism elaborates doctrine very clearly, Catholicism and Christianity at large is not legalistic in spirit and the Bible leaves much for the reader to discern in living out its doctrines. But as Dante, Saint Hildegard and the whole Catholic tradition makes clear, the potential for living and knowing divinity is implicit in man’s nature as the capax Dei. In the very reason that Petrarch, Charlie Brown, and modern man yearn at all is an intuitive shakiness that something isn’t right. In the 6th century Platonist philosopher Boethius explains in his Consolation of Philosophy that even evil is a failure to achieve good because of ignorance and misguidedness, and that the good in itself is the teleological end of all things. Man in his nature strives to set things right.

In poem 359 of the Canzoniere, the only one in which Petrarch and Laura are shown to converse, she comes to him “from the serene Empyrean” and rebukes him for his despair. To console him, she reminds him that the laurel means triumph, that she conquered the world and herself, and that it was through God that this was possible. Grace and victory therefore go hand in hand, and with wordplay, Petrarch implies that Laura’s name bears the laurel, that she is a symbol of victory herself. Perhaps it can be said that in his poems, Petrarch means to portray his own longing for victory in an absolute sense, its seeming unattainability, and its conceptual evolution throughout his life. It is elusive yet the one all-embracing remedy to all his defeats. In ancient art, the Roman goddess Victoria is often depicted holding a laurel wreath to crown a hero. This is the very spirit of chivalry, and it is a universal heroic ideal. The hero strives for the recognition of the noble lady. It means victory, and beyond its vulgar definition it means transcendence. This is inherent in our entire being. We have a sense of our own fallenness. It’s built into our desires, doubts, confusion, laments, and hopes. It’s what keeps Charlie Brown going no matter how many defeats, it’s what drives Petrarch to keep writing, it’s what brought Dante to follow Virgil into the abyss and up the mountain leading to the stars. Modern man might live in a world that makes it difficult for him to internalise the sacred, but he nevertheless has a yearning for it in his nature. What it takes is to confront. Just as Dante did. And like the souls of purgatory, we are beaten down by our confrontation with life and those uncomfortable moments of revelation in which we’re brought face to face with the reality of ourselves. But it is in being beat down, just as God wrestles and puts down Jacob in Genesis, that the greatest transformation occurs. Like Christ on his cross, it is up to us to make that sacrifice and bear our own cross. Through the love that draws man up into the heavens, as Dante and Petrarch for their muses, and ultimately, for God. And like that, the crown of victory is bestowed, a place in the stars is affirmed, the cosmic drama from the fall to revelation comes to its conclusion, and the universe is restored to harmonic perfection.

Bibliography

- Ailura. (2013, September 28) Berlin Siegessäule. Wikimedia Commons. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. Retrieved July 29, 2025, from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Berlin_Siegess%C3%A4ule_8245.jpg

- Alighieri, D. (2003). The Divine Comedy (J. Ciardi, Trans.). New York City: Berkeley.

- Burckhardt, J. (2000). The civilization of the Renaissance in Italy (S. G. C. Middlemore, Trans.). Project Gutenberg. https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/2074

- Burckhardt, T. (2003). Because Dante is Right. In W. Stoddart (Ed.), The essential Titus Burckhardt: reflections on sacred art, faiths, and civilizations (pp. 231-245). World Wisdom.

- Guénon, R. (2004). The esoterism of Dante (S. D. Fohr & H. D. Fohr, Trans.; 2nd Rev ed.). Sophia Perennis.

- Hildegard of Bingen. (2021). The Book of Divine Works (Fathers of the Church Medieval Continuations) (N. M. Campbell, Trans.). Washington, D.C: The Catholic University of America Press.

- Ianziti, G. (2005). From Praise to Prose: Leonardo Bruni’s Lives of the Poets. I Tatti Studies in the Italian Renaissance, 10, 127–148. https://doi.org/10.2307/4603728

- John Paul II. (1998, August 26). General Audience. Vatican.va. 26 August 1998 | John Paul II

- Kwok, S. (2017). The Legacy of Copernicus. In: Our Place in the Universe (pp. 177–184). Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-54172-3_18

- Mendelson, L. (Producer), Melendez, B. (Director), Schulz, C. M. (Writer). (1965). A Charlie Brown Christmas [TV special]. Lee Mendelson Film Productions.

- Nickles, T. (2002). From Copernicus to Ptolemy: Inconsistency and Method. In: Meheus, J. (Ed.), Inconsistency in Science. (Origins, Vol. 2, pp. 1–33). Dordrecht: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-0085-6_1

- New International Version. (2011). The Holy Bible (NIV). Zondervan. Retrieved from Genesis 1 NIV - The Beginning - In the beginning God - Bible Gateway

- Petrarca, F. (1898/2001). To Posterity [pp. 59–76]. In Selections from his Correspondence (J. H. Robinson, Ed. & Trans.; Hanover Historical Texts Project). Hanover College. Retrieved from pet01[1]

- Petrarch, F. (1999). The Canzoniere, or Rerum vulgarium fragmenta (M. Musa, Trans.). Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Piolle, G. (2009, April 25). Fontainebleau - aigle impériale. Wikimedia Commons. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. Retrieved July 29, 2025, from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fontainebleau_-_aigle_imp%C3%A9riale.JPG

- Schulz, C. M. (1957, September 4). Peanuts [Comic Strip]. GoComics. Peanuts by Charles Schulz for September 4, 1957 | GoComics

- Schulz, C. M. (1959, May 17). Peanuts [Comic Strip]. GoComics. Peanuts by Charles Schulz for May 17, 1959 | GoComics

- Schulz, C. M. (1963, June 9). Peanuts [Comic Strip]. GoComics. Peanuts by Charles Schulz for June 9, 1963 | GoComics

- Schulz, C. M. (1975). "Peanuts Jubilee: My Life and Art with Charlie Brown and Others". (p. 84). Henry Holt & Co.

- Schulz, C. M. (1978, May 30). Peanuts [Comic Strip]. GoComics. Peanuts by Charles Schulz for May 30, 1978 | GoComics

- Schulz, C. M. (1993, November 13). Peanuts [Comic Strip]. GoComics. Peanuts by Charles Schulz for November 13, 1993 | GoComics