The Philosophy of Quantum Physics 7: Is Aristotelian Philosophy of Nature Obsolete?

A look at different philosophical interpretations of quantum physics. This is the seventh post in the series.

I am having a look at different philosophical interpretations of quantum physics. This is the seventh post in the series. The first post gave a general introduction to quantum wave mechanics, and presented the Copenhagen interpretations. I have subsequently discussed spontaneous collapse, the Everett interpretation, Pilot Wave, consistent histories interpretations, and quantum Bayesian intepretations.

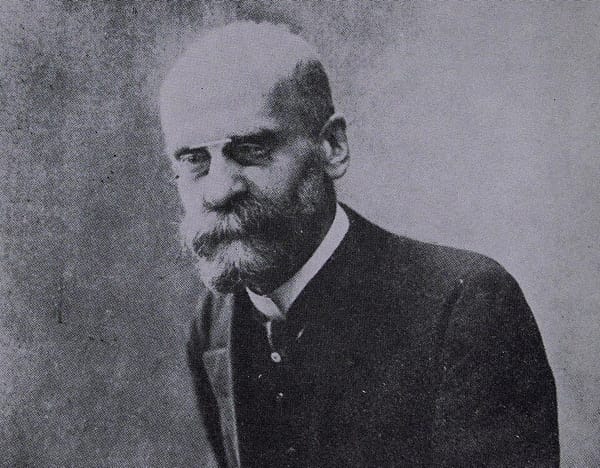

In this post, I am going to do something a little different. The first reason why this is different is that this post is more of a summary and review of a book than an outline of a particular position. The book in question is by Robert Koons, Is St Thomas's Aristotelian Philosophy of Nature Obsolete? This book was released a couple of years ago, and I have been meaning to review it for some time. Professor Koons is a philosopher, rather than a physicist, specialising in Thomistic and scholastic philosophy. Indeed, he is among the world leading contemporary Thomistic philosophers, and a writer who has to be respected.

The second way in which this post differs from my previous ones is that it primarily looks at a different question. There are two fundamental problems that quantum physics attempts to answer.

- Given our knowledge of the present state of the universe, what is the probability that the universe will evolve into a particular future state?

- Given some knowledge of the underlying structure of a material, what properties (macroscopic and microscopic) would we expect to observe for that material.

I will call these the question of dynamics and the question of statics. Quantum physics very successfully allows us to answer both questions (at least if we exclude the effects of gravity). The goal of the philosophy of quantum physics is, or ought to be, to explain why quantum physics is successful, in terms of a proposed underlying ontology and metaphysics.

Most of the interpretations I have looked at so far address the first of these questions, and largely ignore the second. There are perhaps reasons for this: maybe it is thought that once you have an ontology that explains the dynamics, then the statics will fall into place as well. Or maybe the study of statics is just a lot less intellectually sexy than the dynamics: after all, the most obviously weird parts of quantum physics are related to the dynamics. Thirdly, the philosophy behind mechanistic physics contains its own theory of statics, and people naively carry this forward into quantum physics. After all, the weird parts of quantum physics are related to the dynamics, so it is natural to suppose that the statics is unaffected by the movement from classical to quantum.

The question of dynamics is raised first in a physics course (where we start by introducing and solving the Schroedinger equation), and is the topic of the cutting edge of particle physics research. The question we all want to know is what lies behind the standard model to allow us to unify quantum physics and general relativity. Questions are raised in the dynamics, and maybe this is as far as the philosophers of science get. However, a physics student would then move on to spend far more time studying, for example, condensed matter theory or atomic physics, which more concerns the question of statics. These are hugely important branches of physics, and to the physicist they are certainly no less sexy or interesting than the more fundamental questions of physics, where dynamics are more important. But condensed matter physics and other fields are more complex and harder than just solving the Schroedinger equation or drawing some Feynman diagrams for isolated particles. Not in the sense that more brain power is required to perform cutting edge research -- that's about the same between particle physics and condensed matter physics. But it has a higher barrier of entry -- you need to know more before you can start appreciating it -- and it is far more varied and covers a far larger range of phenomena.

However, most philosophers of quantum physics concentrate on the dynamics. This is true of my own work as well as many others. I briefly discuss statics, but not in the depth that the topic deserves.

Robert Koons book is unusual in that it spends a relatively small proportion of the text discussing the dynamics. It still devotes two chapters to it, culminating in a discussion of Pruss' travelling forms interpretation (which Koons advocates), and he does consider the interpretations I have looked at in previous posts. Instead it mainly concentrates on the statics. There is nothing wrong with this approach. It is work that needs to be done.

Obviously, Robert Koons and myself both adopt a similar underlying philosophical background, and as such I find myself in agreement with a lot of his aims and intentions in writing this book. I will discuss how much I agree with his conclusions and how he gets there as I go through the review.

The book has eight chapters.

- Introduction

- The rise and fall of physicalism.

- Hylomorphism and the Quantum World

- Deriving Hylomorphism from Chemistry and Thermodynamics

- Hylomorphism and the Measurement Problem

- The Many-Worlds Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics

- Biology and Human Sciences

- Substances, Accidents, and Quantitive Parts

Is Aristotelian Natural Philosophy necessary and concordant with modern science?

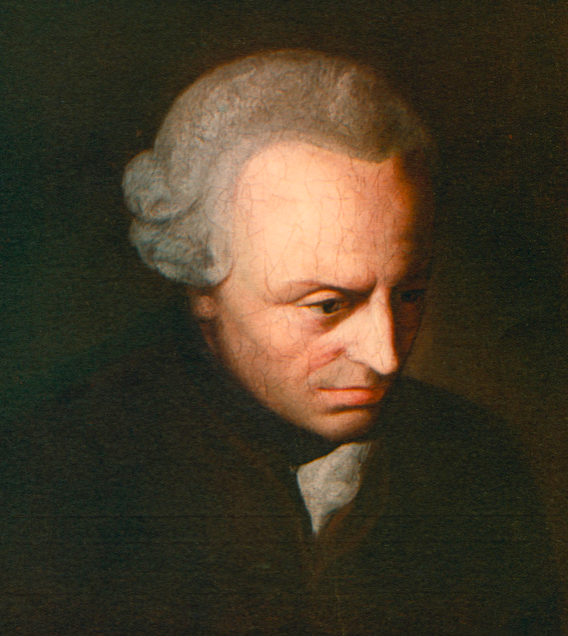

Aristotle's philosophy in general, especially his natural philosophy, metaphysics, and ethics, was neglected for a long period of time. This was due to the rise of early modern mechanism and then empiricism, which initially promised to be a powerful explanatory mechanism working in tandem with the science. However, modernism didn't fulfil its early promise, or offer us with all the answers. In the last forty years or so, quite a few philosophers have turned back to Aristotle and his medieval successors to see if they can offer a better solution to the problems of modernism than following the post-modern and counter-enlightenment world-view. Developments have been made in particular in ethics and the approach to science.

In particular, Professor Koons will concentrate on hylomorphism, the form-matter distinction that lies at the heart of Aristotle's philosophy of nature, metaphysics, and epistemology.

But, Koons argues, this is all for nothing if the challenge from modern science cannot be overcome.

So, we must ask two questions: can we have an Aristotelian metaphysics (a theory of being as such) without an Aristotelian philosophy of nature? And can we have an Aristotelian philosophy of nature without Aristotelian natural science?

To answer Yes to either of these questions would be to cut Aristotle's philosophy (and successors such as Thomism) off from natural science. It would be to adopt either Aristotelianism without hylomorphism, or to suggest that hylomorphism has no implications for the practices of the sciences. This makes Aristotle's philosophy unfalsifiable. Convenient for those who want to work without any great trouble, but hardly an approach which will endear itself to a mainstream scholarship sceptical of Aristotle's metaphysics.

Professor Koons suggests that we should answer both questions No. I would agree with him. In my view, to answer the first question Yes cuts out a core part of Aristotle's system, and destroys its internal consistency to an extent that one's philosophy can no longer really be regarded as Aristotelian. Professor Koons notes that it would undermine the doctrines of transubstantiation (which, as a Protestant, I would reject anyway, but it is important for Roman Catholics such as Koons), and the union between soul and body in a living creature (which I do agree would be a problem). The second question should be answered No. Aristotelian philosophy has always been empirical in nature. It might have slightly different aims to modern science, and less precision and certainty, but it is applied to the same objects. Hylomorphism's search for essence and modern sciences search for mathematical laws seem different, but could just be the same end discussed in different ways. Aristotle's natural science is certainly different from a positive or Humean conception of science, but those perceptions are just modern theories about natural science, not natural science itself.

So instead, Koons rightly concludes

Our natural philosophy should be continuous with our natural science, albeit at a higher level of generality and a deeper level of philosophical explanation. This does inevitably entail that Aristotelian natural philosophy (and so, ultimately, Aristotelian metaphysics) is in principle falsifiable, or at least subject to disconfirmation by empirical results. Now I think this is a plus.

Koons believes, that unlike classical physics and chemistry (from Galileo to Rutherford) which seemed to be against hylomorphism, the quantum revolution of the twentieth century is consistent with it, and in fact provides empirical support for it. The conflict was never between hylomorphism and modern science, but between hylomorphism and a certain philosophy of science. That philosophy of science developed alongside classical physics, and as classical physics was proved to be more successful than Aristotle's physics, it was natural that people should gravitate towards what Professor Koons calls microphysical materialism. But things have changed since the quantum revolution in physics. This challenges microphysical materialism in various and profound ways, and thus ought to have led to a change of perspective on the philosophy. However most philosophers, and even most physical scientists (who rarely pay much of an interest in philosophy) have not appreciated this. The new image of nature has revived an Aristotelian understanding across a wide range of scientific disciplines.

This claim obviously needs to be backed up, which is what Koons will attempt to do in the rest of the book.

Read the rest: https://www.quantum-thomist.co.uk/my-cgi/blog.cgi?first=103&last=103