The Ascension, and Will of Heaven

We have a moral prerogative, an instillation within our nature, a call of destiny, that those of us, those of us with ability–or with the impetus to seek to become capable–must thoroughly transform and be the bedrock and foundation of our culture.

Culture

- We have a moral prerogative, an instillation within our nature, a call of destiny, that those of us, those of us with ability—or with the impetus to seek to become capable—must thoroughly transform and be the bedrock and foundation of our culture. In eschatological perfection, within the forgetting of human life as we approach the mystical altar, there is no difference between first and last (Galatians 3:28); “all things join in unity”. However, within the fallen bed of existence, considering the difficulties and grand impact of human affairs, if it accords with propriety to act, and one indeed possesses greater ability than their peers—and yet refrains from responsively acting—this may be termed “neglecting duty”.

- So, the Book of Changes (易經) says,

“Wind blowing up in the sky is small nurturance (Hexagram 9); thus do superior people beautify cultured qualities”.

- The lower aspects of culture emanate naturally—must be allowed to be preserved in their natural procession—but must take a lower position to the higher and highest aspects of culture. The development and creation of the highest aspects of culture spontaneously derived from the spiritually cultivated, or intentionality, accompanied with careful adherence to the pattern-principle of heaven. Ultimately, when culture is properly cultivated, it becomes equivalent to pattern-principle; beauty becomes reflective of virtue. The concepts of “pattern-principle” and the precedence of virtue over beauty are Neo-Confucian ideas and are explained in the works of Zhu Xi.

Knowledge and Harmony

- The Explanation of the Diagram of the Great Ultimate (太極圖說) by Zhou Dunyi says,

“It is the human being alone who receives the best of all and is the most intelligent. At the moment of formation, his spirit develops consciousness. The five moral principles of his nature are aroused by and in reaction to the external world and engage in activity; good and evil are distinguished; and human affairs take place”.

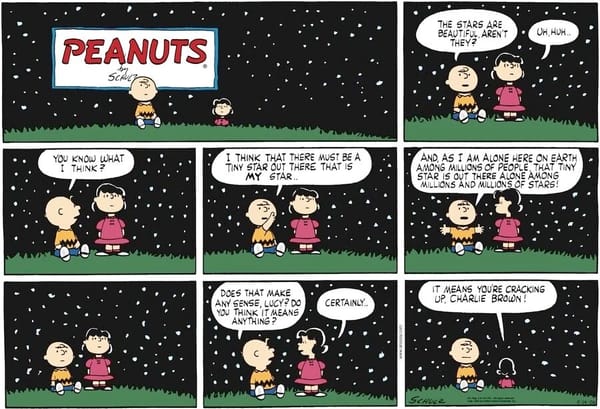

- Knowledge is intrinsically joined with being and being is joined with harmony: if our knowledge is not substantiated on being in harmony with those around us, with the uncountable living creatures, trees, celestial bodies—not to mention moral and divine principle—then both our knowledge and human affairs will be in disarray.

- When knowledge is in disarray, there are many names and little understanding. When knowledge is in order, all names form a replicating unity; so it is as though there were few names. Those unfamiliar with the knowledge that knowledge itself should follow principle consider a multitude of names to be the very symbol of wisdom; but those that are wise consider many words and complex names to be a waste of breath.

- The incomprehensible is that which is the foundation of the comprehensible. The unity beneath all unities is in itself that which contains all names and is the source of that principle by which knowledge and all things are regulated. So, it is said, “the spirit steadies itself above the nine heavens” (Lu Dongbin).

- At the pinnacle of deepest darkness and obscurity, above the shimmer and gleam of every good principle and word, what do we find? It is said that only in the apophatic gaze, does true light—that which is without substantive root but is instead the substantive root and web—emanates and transforms us. The transformation of Heaven, or the miraculous work thereof, is mysterious and wonderful. The entry point by which one is transformed is called responding to Heaven’s will.

- The twin achievement of the human being, the figurative dwelling in repose, the restoration of the correct advancement and course of emotions; can be summarised in attaining balance and harmony. A balanced person is one who takes unity and holds it fast to their breast, like a man in rough hemp carrying a gem, therefore they “can never be moved” (Psalm 111). A person of harmony is someone who may act spontaneously; yet all their actions and the very outstretching of their arms are correct.

- Balance refers to tranquillity; harmony refers to the correct blossoming of emotion and act. Comparatively, these refer to the Platonic-Aristotelian Christian ideas of purity—in reference to tranquility, and justice-charity in reference to harmony. The twin attainment of balance and harmony applies not just to emotion or virtue; but virtue-emotion referent to affairs. Affairs constantly grow, self-multiply, and the more one seeks to grasp them, the faster they slip away.

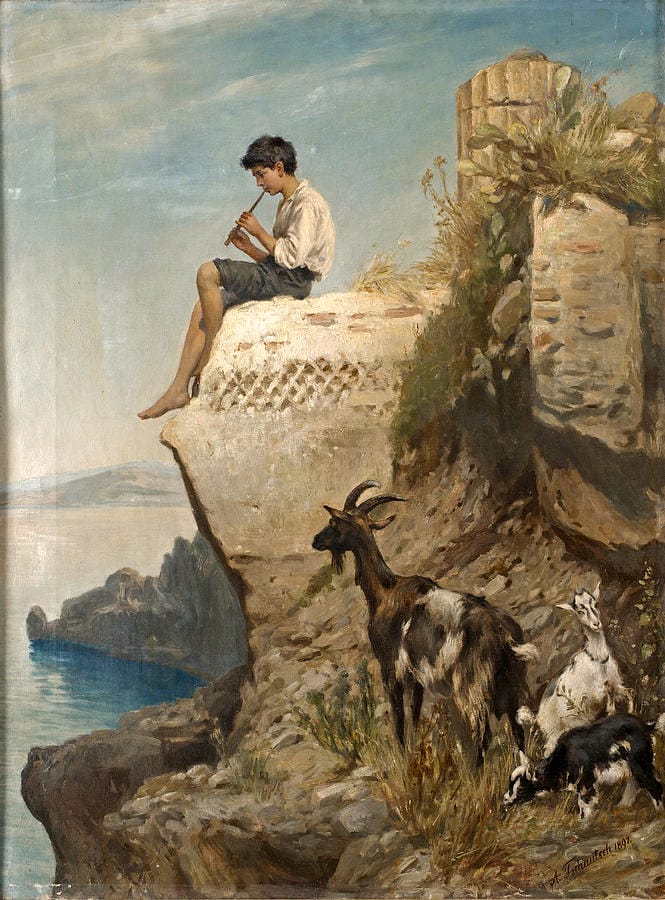

- Attempting to grasp affairs can be likened to a shepherd boy, who, in haste and will to recover the wayward and scattering members of his flock, like ash breaking into dust and smoke, takes to his feet and exhausts himself, chasing one after the other—just to lose each again—instead of settling feed and water at the centre of their habitation and retrieving them by their own natural tendencies.

- To deal with affairs, one must first establish unity, then human and earthly affairs will automatically be dealt with. To seek to attain unity is always primary; all other approaches can be considered subsidiary methods.

Emotion and Reason

- Emotion itself is an act; more accurately is an act of spirit: an agitation or disturbance or ultimately a temporal motion and expression of spirit (and spiritual energy). Therefore, it is not simply that emotion is linked with action and human activity, but that emotion is itself a primary act.

- Emotion and rationality cannot be thoroughly divorced as they are both linked to the innate moral agency of humans—that is, humans are intrinsically and primarily moral agents (even more determinably than our arms and legs and conscious formulations—that is, the human is the moral and virtuous animal: in the way birds take wings for their identification and lions take manes for their dignity, humans find their most accurate delineation in their propensity for virtue.

- Rationality is the constant consideration of the good and proper; and emotion is the elicitation (of action) and response (essentially so) to those elements. Since the ultimate object of their consideration (in terms of human nature and spirit is the same, they cannot be utterly bifurcated or severed. Instead, it is with the complete consideration of rationality and the illuminosity of knowledge that emotion finds its full, most potent, indomitable and divine expressions; and it is with the starting point of human emotion that one can discover rationality and moral principle in the first place.

- The reunification of emotion and reason—or the recognising of them as already implicitly so—can be taken as signification of the complete transformation of the human person: That is, someone who can be called a true person. Transformation is the basis of ethics and ethical systems. It is the transformation prodded by the singular and multiplicative act of grace and divine virtue that serves as the referent and object of testification of ethics.

- Ethical meanderings are often beautiful, in the same way discussions of God or love are always beautiful: for they are the codified expressions of love within a real existence—perhaps, because divine transformation itself is begun, continued and consummated by love. Yet, to discuss ethics without considering a real person or a human being appears to be the presentation of upside-down words.

- The beginning of such conversations seemingly ignores the fact that there can be no ethics without a person codified by love—a real being—whether God (as in Thomist tradition) or in Mozi’s constant references to the benevolent people of the past. The consideration of ethics otherwise can be indicative that emotion and reason have once again been artificially separated.

Beauty and Cultural Representation of Virtue

- From a wider perspective in society, beauty and cultural representations of aesthetics are the expressions of love (descriptively codified within ethics). Of course, what we love in beauty is the goodness emanated by love, and what we find beautiful is love itself.

- The issue associated with beauty is that it takes its primary contextual relevance in the fact that it is generally apprehensible to perception and therefore only intuited from external stimuli; that is that beauty is primarily perceptible from sensory data and is therefore separable from its natural foundations in love, ethics and virtue. When beauty is no longer conjoined with virtue, that is the beginning of sorrow in society.

- Today, we have the responsibility to first cultivate ourselves and then cultivate others. The purpose of Ninth Heaven is to be a terrace—that is, a grove lined with leafy trees and clean pavilions—where people can walk down and be enriched, taking in the flowers and fruit, to enrich others; and to enrich the ascension of cultural acuity and virtue in society.