Respecting Antigone

This is the commiserating heart that is both rare and common: common as in all men and women possess it; rare as in few bring it to finality. Antigone was able to maintain her original heart and develop her virtue, immortalising herself and her love for her loved ones.

O father, poor tormented Oedipus,

my eyes can glimpse, off in the distance,

walls around the city. This place, it seems,

is sacred ground clustered thick with grapevines,

with laurel and olive trees. Inside the grove many feathered nightingales are chanting their sweet songs. Sit down and rest your limbs

on this rough stone. For a man advanced in years you have come a long, long way.

– Ian Johnston, Vancouver University. Oedipus at Colonus

Pre-exposition on Tragedy

Greece is a mysterious place—or so it has been said. To drink of the Greek ragedy and mythological records: the sculptures, engravings and monuments dedicated to the long-fallen Grecian heroes—cannot taste but sombre, sombre and slight, slightly sour; the sensory apprehension and youthful delight of the sun-hued golden apples of the Ἑσπερίδες, that is the Hesperides. Such wine settles the spirit, rejuvenates the bones and sits you down at an old rickety table, and entombs you in the form of an old Greek peasant returning home in the evening from his life: it takes your knife, placing it upon splintering wood, and dims your eyes. For in that person we find the metaphor of life—readily existent and ready with the constant heaviness at its root—or the apprehension of such due to sympathetic commiseration. This can be termed a kind of death or dying for another–or dying in the death of another–and this death can be termed a sort of rebirth, and within the process, a refining of will and spirit, spirit and character, character and resolve.

For how can a person who has experienced tragedy in the very life they call their own—no, even yet they who boasts proudly and proudly boast of having no weakness, no sympathy with another cannot—take a swig of the song and suffering of that Achaean hero (that is Ἡρακλῆς, Heracles) and not feel deeply within themselves, upon the very pivot of their soul, that a-typical heaviness of the night, the darkening shadows of blue evening. Yes, there is not a single person, not one—with heart or formless cavity—who within is not taken by grief or does not take upon themselves moods and memories, sombre and sorrowed, upon recollection of the many toils and tribulations of that man struck by madness and readily subjugated to toils of unceasing labour, and condemned to achieve what men would reckon impossible feats, to atone—for the slaying of his wife and children—that is, truly for the extinguishing of his own life.

“But again, Tragedy is an imitation not only of a complete action, but of events inspiring fear or pity. Such an effect is best produced when the events come on us by sunrise; and the effect is heightened when, at the same time, they follow as cause and effect.”

– Aristotle, Poetics Ch. IX

Indeed, the grief that already wounds from beholding suffering can yet be compounded; may be but further multiplied upon the comprehension of the recipient, the one suffering. It is already of grief to behold the suffering of another; it is of yet of more grief that a good man should suffer. To hear of a person suffering is as to take an arrow to the chest; to hear of a good person suffering is as to be impaled by a barbed javelin. When we perceive those we hold to be selfless, kind, good and heroic in dire straits—being dispossessed and thrust into continual and unrelenting suffering—it is natural that we cannot prevent the formation of tears rushing to our eyes.

“Then he sang how the Achaeans left their hollow hiding place, and poured from the horse, to sack the city. He sang how the other warriors dispersing through the streets, laid waste high Troy, but Odysseus, the image of Ares, together with godlike Menelaus, sought Deiphobus’ house. There, said the tale, Odysseus fought the most terrible of fights, but conquered in the end, with the help of great-hearted Athene.

So sang the famous bard. And Odysseus’ heart melted, and tears poured from his eyes. He wept pitifully, as a woman weeps who throws herself on her husband’s dying body, fallen in front of his city and people…”

– Kline, Odyssey, Bk VIII

The tragedy speaks and beckons, considering the seriousness of life. It sombres down and it stirs up empathy. It unburies, it removes the surface and shakes off the dust of temporal obsfuscation to reveal that which is nascent and buried within. This empathy, brought to light, begins the real apprehension of love; the complete identification with another. Although it may appear painful to begin with, like a mother in the pains of childbearing, it is necessary for the formation of new life, joy and green birth. Indeed, like the world in its constant rotations, the emotions of summer, autumn, winter and spring cannot be removed, and it is primarily in winter that one comes to terms with who they are, that one feels the cold biting their bones and gnawing deep in their marrow, that one comes to terms with weakness and mortality and sorrow. Tragedy illuminates these emotions, like four apertures illuminated in light, like the upper clerestory of a cathedral taking the glory and grace hidden with the sun, and with it, tracing suffering and form to bring divine glory to human existence.

Antigone

Of those who have experienced the painful thorn, the wet cold saturation and burning distortion—the seemingly cruel resignation of tragedy and happenstance, and yet still persisted in an out-florescence of love and love-bound beauty—of how many can compare to Antigone? She was burdened and counted it not so, with love to the point of death for her nearest kin, for her only family, and served as a model for filial piety.

Context of Filial Piety

Although filial piety is commonly associated with the Han-derived states, it is my assertion and particular emphasis on the following two contrasts: firstly, this is a case resembling Guo Jujing's 24 Paragons of Filial Piety, albeit it in in pre-classical Greece rather than China, and secondly concerning filial piety in women rather than men. It is not intended to imply that there was an absence of filial piety analysed, admired or expounded in regard to women. Contrarily, Zhu Xi and Yangzi both go through several examples. It is simply meant, in addition to the discussion of Antigone, to highlight the contrast.

“(Once), when Zhong Ni (Confucius) was unoccupied, and his disciple Zeng was sitting by in attendance on him, the Master said, "The ancient kings had a perfect virtue and all-embracing rule of conduct, through which they were in accord with all under heaven. By the practice of it the people were brought to live in peace and harmony, and there was no ill-will between superiors and inferiors. Do you know what it was?” Zeng rose from his mat and said, "How should I, Shen, who am so devoid of intelligence, be able to know this?"

The Master said, "(It was filial piety.) Now filial piety is the root of (all) virtue, and (the stem) out of which grows (all moral) teaching. Sit down again, and I will explain the subject to you.…”

“…The Master said, "The service which a filial son does to his parents is as follows: In his general conduct to them, he manifests the utmost reverence. In his nourishing of them, his endeavor is to give them the utmost pleasure. When they are ill, he feels the greatest anxiety. In mourning for them (dead), he exhibits every demonstration of grief. In sacrificing to them, he displays the utmost solemnity. When a son is complete in these five things, (he may be pronounced) able to serve his parents.”

– James Legge, Xiao Jing (Classic of Filial Piety)

The topic of filial piety is a complicated, easily misunderstood topic and is not intended to be discussed here. This is simply intended to serve as pre-liminary, that is, contextual information.

Sophocles, Oedipus Rex Tri-Drama

Aristotle does not shy away but instead deigns to mention the eponymous tragedy of Sophocles, the now slandered Oedipus Rex—of which now we are inundated with what can only be termed a babble, a resurrected and delusional clay tower of Babel termed a pyramid, that is those psychoanalysists—there we first make familiarity with Antigone, daughter of an abandoned babe, a child left on the mountainside, the Corinthian boy entangled by fate and hard-suffering. That seemingly accursed Theban Monarch, by the blessing and the mercy of God, at least found that last reprieve in the constant sincerity and steadfast love of his daughter.

It is difficult to describe the admirability of Antigone.

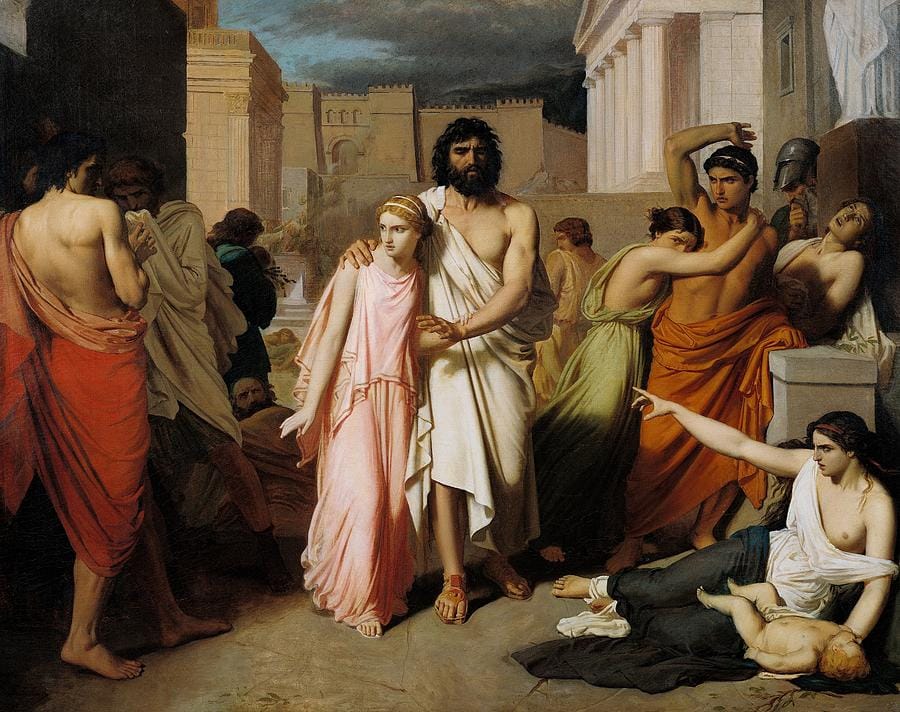

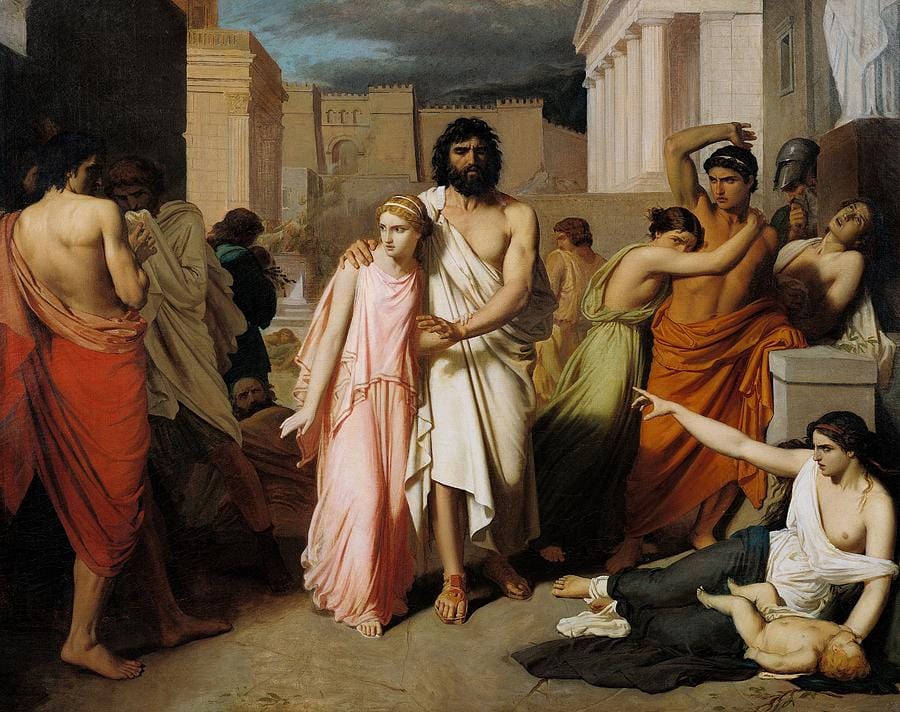

We first see her at Colonus with her father, the latter now in a life of bitterness and exile, supporting him upon her arm and guiding his eyes; once seeing, now blind. The image of a princess, a noblewoman, who has abandoned the palace, abandoned marriage and prospective suitors, abandoned wealth and comfort—to follow her blind and disgraced father into exile and ostracisation. As a young woman, how can it be easy to leave everything behind?

Yet, her father soon dies and she is thrust into the power struggle of her two irresponsible brothers who violently vie for the succession of his old throne. The younger, Eteocles, elevated by the people, fought in defense of the city and his new dominion. His brother, Polyneices, formerly in exile, returned with the support and the violence of a foreign alliance (so goes the story of the Seven Against Thebes). Unfortunately, the conflict would end with the death of both her brothers at the hands of each other.

The Tragedy of Antigone

The tragedy of Antigone, the true tragedy of Antigone, came in the form of the last Theban play written by the poet and playwright Sophocles. It is a tragedy that belongs to her first and foremost, most poignantly and painfully. Like said in the Poetics, Tragedy is an imitation of those events bound and unified by cause-and-effect and inspire man to pity or sorrow. In this tragedy, one comes face to face with the sorrow and resolve of Antigone.

The prelude is as follows:

Upon the death of Antigone's two brothers, it was mandated by Creon, new ruler of Thebes, that Eteocles should receive an honourable funeral, and his brother Polyneices should be left strewn on the field to be eaten by birds. This mandate was exercised under pain of death. Obstinate, Antigone refused to abide according to the mandate and was soon discovered laying handfuls of earthen soil on the corpse of her brother. Upon given warning and chance to repent, she refused, saying:

"If my husband were dead, I could have another, and if I had lost a child, I could bear another from a different man. But with my parents in the house of Hades, no brother could ever live again.”

“It was not Zeus who made that proclamation; nor did Justice, dwelling with the gods below, ordain such laws for men. Nor did I think your decrees were of such force that a mortal could override the unwritten and unfailing statutes of heaven.”

"I shall lie with him in death, and I shall be as dear to him as he to me. I have committed a crime, but I do not feel guilty. For I was born to share in love, not in hatred."

"But Polyneices was my brother too.”

For the sake of her love and affection for her brother, she readily sacrificed her life. For the sake of comforting her parents, she readily took on their suffering. Upon seeing her brother's corpse strewn and dead on the fields, she could not bear to leave him without proper funeral, even to the point of her own death. How many people can be led by their true emotions to this degree? How many can exercise bravery and stand for what they believe is right–even to the point of death? How many can follow their natural love for their family?

This is the commiserating heart that is both rare and common: common as in all men and women possess it; rare as in few bring it to finality. Antigone was able to maintain her original heart and develop her virtue, immortalising herself and her love for her loved ones. I write this in the wish that all can respect Antigone and take on admiration for her, seeing her as a model, an exemplar for filial piety.

Paying respect to the worthies, long gone in the past.

Paying respect to Antigone, daughter of the Theban King.