Black Box

A short fiction piece about a girl, a girl, a hallway, a kitchen, and perhaps another glass of wine.

“Think of a kitchen table then,” he told her, “when you’re not there.” Virginia Woolf, To The Lighthouse, 1927

Black Box

The aperture of a door opened narrowly on the dark. Claudia held out her hand and the finger-shapes blotted out the light. Behind her, an identical portal loomed. She faced a wall, or where she remembered a wall to be.

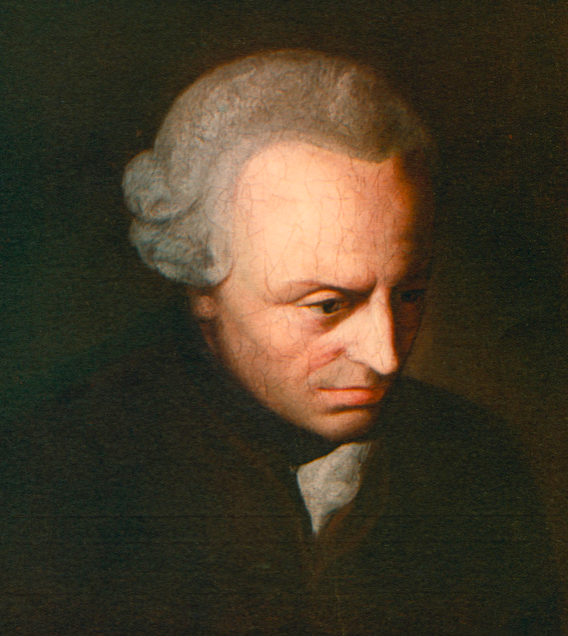

She could not see the wall, and in an instant, the veil of her memory was lifted from her visionary imagination. The off-white finish, divided into thirds by the wainscotting and the landscape painting hanging from the rail, disintegrated into the darkness.

The shapelessness seemed to take on definition. In front of her was a landscape, not a painting of a landscape. It stretched out in blue-grey swathes of invisibly undulating land. Receding into the blue-grey of the horizon and lifting into the blue-grey of the sky. She could feel the cool-wind and smell the smells that the cool-wind lifted and carried to her in the dark.

Claudia looked side to side. She could not remember through which portal she had plunged into the darkness.

She entered the kitchen. She saw how the laminated bench fringed the wall in an L, and that the windows were opaque with steam from the sink. White rims of plates rose from the clear-grey water. Laura stood by the stove, surrounded by the smells and the noise of ingredients on hot pans.

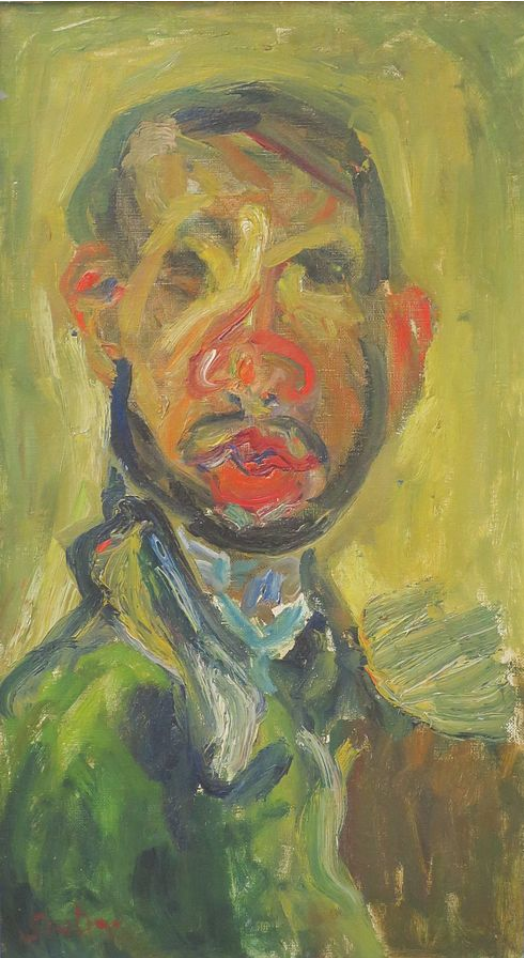

Claudia palmed a bulb of garlic with her hand. She dipped the fingers of the other into the clear-grey water. The skin of the garlic was dry and papery. The skin of her fingers in the clear-grey water were wrinkly. She thought of dipping the papery shell into the clear-grey water to see if it would wrinkle, too. But she didn’t. She placed the garlic on the cutting board which was stained by the juices of the ingredients on the hot pans. The knife by the board was silver and glowing. It was the lights in the kitchen that made it glow. It looked like a piece of molten steel, or a shard of the Sun. She could foresee the motions of the knife cutting the garlic, but she imagined that the papery skin would be burnt up by the Sun-knife.

Laura turned round. Her cheeks were red. Claudia knew that sometimes people’s cheeks turned red when they had exerted themselves or were embarrassed. But she could not imagine that Laura was embarrassed by onions cooking in red wine. The bottle of red wine was by the pan. Laura said that everything was coming along nicely—no thanks to that lot. She poured Claudia a glass. The red wine was fruity and warm. Not as warm as the clear-grey water: blood-warm. Claudia’s cheeks were red.

Claudia had had a finger of the red wine. She enjoyed the blood-warm temperature in her throat. Her cheeks and chest were now a blood-warm temperature. She did not want to be like that lot. Could she help with anything? No, not at all, but if she wouldn’t mind, she could cut two cloves of garlic. Thank you very much, darling.

The knife was in her hand. Her wrinkly fingers looked absurd gripping the smooth-black of the handle. She was worried about the skin of the garlic going up in flames. The lights in the kitchen made the knife glow. She had had perhaps two fingers of the wine. She imagined the motions of the knife: precise, graceful sweeps of the blade. She imagined the two cut-cloves of garlic in a neat pile on the board on the juices of the ingredients that were on the hot pans. Outside the opaque windows, the streetlights were on; the opaque panes were frost-white. But it was a summer night. She made the motions she imagined the knife would make.

The smells of the kitchen lay on top of each other and lay over the kitchen. There were smells of herbs and meat. It was a summer night. There was a summer heat in the kitchen. And would she please open a window? It was hot as Hell in here. Claudia opened the window, because Laura had asked, and it really was as hot as Hell was.

She had had thoughts of Hell as a young girl at church. The kitchen was not a church, but it was like a church through associations: the red wine, the opaque panes, the sepulchral white of the bench. Claudia wanted to confess something to Laura, like she had done as a young girl at church. But she did not know if Laura and she were close enough for a confession. Would Laura appreciate the confidence? Claudia had a blood-warm feeling for Laura; she wanted to protect her from that lot and Hell-heat. Because Laura was here, in the kitchen-church, pouring her red wine of which she had had perhaps three fingers.

But what could she confess? Claudia remembered the things she had confessed as a young girl at church. She had confessed for taking her sister’s silver bracelet without asking, and for sometimes wishing she did not have a sister. But she had not taken the silver bracelet. Her sister had moved to Melbourne. So, she no longer wished not to have a sister.

Finally, she confessed to Laura that she was reminded of the poem “Church Going” by Philip Larkin. She said that the line, “Up at the holy end,” fit Laura by the stove. That what she was cooking smelled heavenly. Claudia did not confess that the line she was actually thinking of was: “In whose blent air all our compulsions meet.” She did not want Laura to ask which compulsions she had.

Laura laughed lightly and said something about poetry being over her head, you know? Her light-laugh rose over her head and settled among the vaulted church ceiling of the kitchen. Would she like a refill? She poured four more fingers of the red wine.

And that lot would probably want something to chew on. And would Claudia please take that tray out to them? Thank you very much, darling.

In the dark, she listened to the red wine lap against the sides of the glass in her hand. She balanced the tray in the other. She did not see what she held. The memory of what she held in her hands became untethered from her sensations.

The flat plain of the tray seemed to stretch out infinitely: the bedrock of an unmade-Earth. And over the plain she would pour out the ocean she held in her other hand. She could hear the waves lapping against the lee shore.

She began to sway, like the perhaps five fingers of red wine gripped her shoulder and gently rocked her.